Promising signs for disorder affecting children of Quebec and beyond

There are few disorders that contain the geographical region where they were first discovered in their title, and Autosomal Recessive Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix- Saguenay (ARSACS) is one of them. The disorder, which has since been identified in 12 countries, is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily affects the cerebellum - the brain’s centre for movement and coordination.

There are few disorders that contain the geographical region where they were first discovered in their title, and Autosomal Recessive Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix- Saguenay (ARSACS) is one of them. The disorder, which has since been identified in 12 countries, is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily affects the cerebellum - the brain’s centre for movement and coordination.

Symptoms appear when infants start to walk, causing them to stagger and fall more often than normal. As years pass, symptoms worsen, including poor coordination, stiffness, muscle atrophy and slurred speech. By their early forties, most patients are wheelchair-bound and life expectancy is reduced.

Back in 2000, scientists first identified the gene known as SACS, which is associated with the disease. SACS produces a protein called sacsin, but until now, the role or the function of the protein was unknown. New collaborative research led by Drs. Bernard Brais and Peter McPherson of The Neuro, and Paul Chapple at Queen Mary, University of London, indicates that that the sacsin protein has a mitochondrial function and that mutations causing ARSACS are linked to a dysfunction of nerve cell mitochondria – the ‘batteries’ or energy-producing power plants of cells.

This latest research significantly increases understanding of the disease and reveals an important common link with other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases, providing renewed hope and potential for new therapeutic strategies for those affected. “Now that we know what the protein’s function is, we can screen for drugs. Pharmaceutical companies won’t start drug screening for a disease with only a few thousand patients, but as they screen for drugs that might be effective for Parkinson’s disease, it’s possible they’ll find drugs that could reverse some of the defects in ARSACS”, said Dr. McPherson.

More than 100 different mutations are known to cause ARSACS in countries such as Japan, Turkey and across Western Europe, making ARSACS one of the most common recessive ataxias internationally. Genetic tests for the mutation are readily available. Although treatment can help to alleviate some of the symptoms of ARSACS, there is no cure.

ARSACS was first identified in the late 1970s in a large group of patients from the Charlevoix and Saguenay regions of Quebec, where the incidence of ARSACS is one in 1,500 - 2,000 births. One person in 21 in the region carries a recessive mutation in the gene that produces sacsin.

ARSACS was first identified in the late 1970s in a large group of patients from the Charlevoix and Saguenay regions of Quebec, where the incidence of ARSACS is one in 1,500 - 2,000 births. One person in 21 in the region carries a recessive mutation in the gene that produces sacsin.

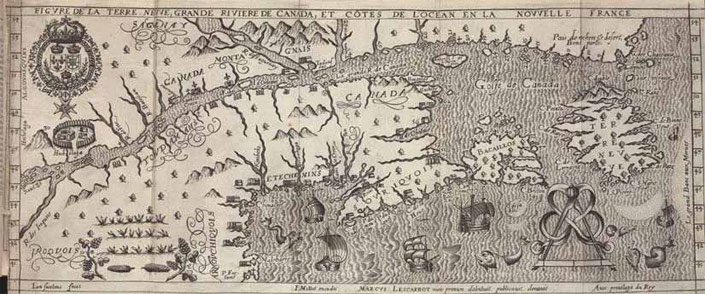

The mutation is believed to have been introduced to the region by a few early French settlers to the area. There is a 50 per cent chance that children of two carriers will inherit the mutated gene, and a 25 per cent chance that the child will develop ARSACS. With the regions’ populations living relatively cut-off from other communities for hundreds of years, the mutation was transmitted through the generations, though remaining mostly within the Charlevoix and Saguenay.

The Neuro’s breakthrough research was funded in part by the Fondation de l’Ataxie de Charlevoix-Saguenay, founded in 2006 by Sonia Gobeil and Jean Groleau, whose two children have been diagnosed with ARSACS.