A hide-out for viruses in the testicles

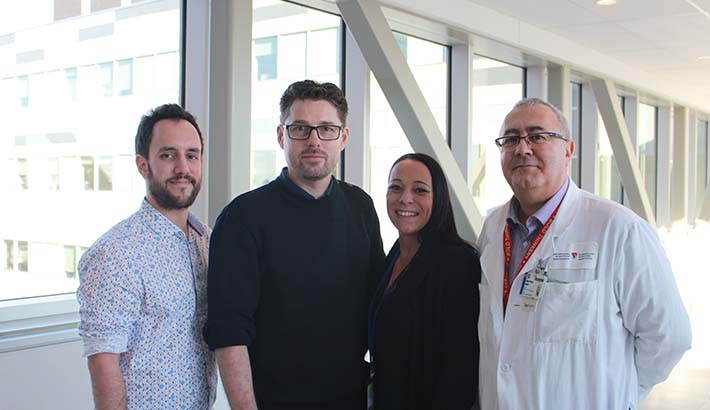

It all began five years ago at the Royal Victoria Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) with one of Dr. Jean-Pierre Routy’s HIV patients.

Gloria, who was born a male, wanted to undergo sex reassignment surgery. The clinician scientist had the surprising idea of asking his patient to use the testicles for research purposes, instead of discarding them. This donation allowed Dr. Routy, who is a hematologist at the MUHC and an HIV specialist at the Research Institute of the MUHC (RI-MUHC) and McGill University, to begin an innovative project that shines new light on the mechanisms of immunity in the testicle.

The “Immune Privilege”

“Testicles are characterized by what is called an ‘immune privilege,’ just like the eye or the brain, which are considered organs with restricted access, relatively independent of the rest of the body,” says Dr. Routy. “In other words, they are separated from the immune system by an anatomic barrier, and the inflammatory response is blocked.”

The immune privilege in testicles ensures that spermatozoa, developed at puberty, are not recognized by the immune system as foreign and are not consequently attacked and eliminated. Dr. Routy notes that about 20 per cent of cases of infertility in humans are due to a breach of this immune privilege, when sperm are destroyed by the surrounding immune tissue.

There is a flip side with immune privilege, however. Some viruses, like Zika or Ebola, find safe harbor in the testicles. Even after healing, these viruses may only persist in the eye and testes—two organs with immune privilege.

Dr. Routy and his team discovered that HIV also uses the immune privilege in the testes to its own advantage.

“The fact that the virus persists in the testes is problematic as it can lead to secondary viral transmission through sexual activity,” Dr. Routy explains. By studying the tissues of six HIV-infected patients receiving triple therapy, the researchers found that the virus, although undetectable in the blood, was still present in the testes. The results were published in the journal AIDS in 2016 and Journal of Reproductive Immunology in 2018.

Donating your testicles to science

To advance this work, it was necessary to study testicles more closely. But first, of course, they had to find some. The testicle is an under-studied organ because it is very difficult to obtain for research purposes. “Most samples come from donors deceased as a result of an accident or from cancer patients,” says Dr. Routy. “I must have been one of the first to ask for such tissues!”

Due to a unique partnership with Dr. Pierre Brassard, surgeon and director of the Montreal Metropolitan Centre of Surgery, the research team was able to recover more than 110 pairs of testicles thanks to donors undergoing sex reassignment surgery (change of male to female anatomical sex) and project funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Kayla McConnell is one of the patients without whom this research could not take place. Approached by Dr. Brassard and his team before her operation, she promptly gave her consent to participate in the study.

“I was immediately interested, as I’m fascinated by the medical field. Not all superheroes wear capes; some wear white coats!” says Kayla. “These people are unique and talented. Not only do they change lives, but they save them.”

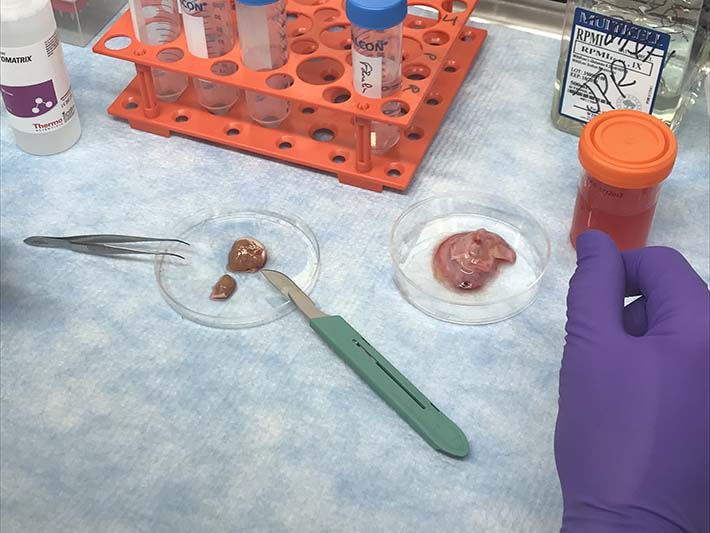

Testicle samples collected for the study come from subjects with and without HIV. Immediately after surgery, the samples are sent to Dr. Routy's laboratory at the RI-MUHC, where research associate Franck Dupuy, PhD, coordinates this work. It’s the beginning of a long process during which the tissues are finely ground and digested with enzymes, then sorted to extract the immune cells and study their functionalities.

“It's an extremely stimulating project because it's a fresh field that needs to be explored. Everything we discover is new,” says Franck Dupuy. “Working on this type of tissue is quite technical. It was necessary to prepare the groundwork and do a lot of tests at the start.”

In the course of their work, the researchers found few immune cells in the testes. “Only 2 to 10% of immune cells are found in the testes. You have to start with a minimum of 40 to 50 million testicular cells to extract these immune cells and test them,” the research associate explains.

Implications for other diseases

According to Dr. Routy, some cancers spread by using the same mechanisms as testicles to protect themselves from attacks by the immune system. The link between cancer and the immune privilege of the testes is not new. “Studies have shown that in children with leukemia the disease is more likely to recur in boys than in girls,” says Dr. Routy. “In fact, the cancer cells took refuge in the testicles of the young patients, where drugs do not penetrate as well.” The researchers recently observed the presence of PD-1 protein on immune cells, or T cells, in the testes. The PD-1 protein, which is widely studied in immunotherapy to treat cancer, acts as a switch by slowing down or stopping the immune system in this region. “The mechanisms of immunity that make up the immune privilege are the same as those used by cancer cells,” says Dr. Routy. “By widening our research on the testes, we hope to better understand how HIV and cancer escape the immune system so we can find new ways to fight both of these diseases.”

Dr. Routy has dedicated his career to the fight against HIV/AIDS, both with his patients and in his laboratory. For years, he has been studying mechanisms of immunity and trying to understand why and how viruses such as HIV persist in the body.