Cracking the Genetic Code of type 2 diabetes

Once you have diabetes, it is difficult to stop its progression and once diabetic complications set in, they are usually irreversible. Diabetes itself is difficult to live with but “death from this disease tends to be from diabetic complications, such as heart attack, stroke, and kidney disease,” explains Dr. Michael Tsoukas, endocrinologist and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) and at its Research Institute (RI-MUHC). Dr. Tsoukas is an investigator with the research team working on a new study to identify genetic markers associated with type 2 diabetes. The study is taking place at the RI-MUHC in Montreal and will be carried out in collaboration with Harvard University.

Our study is part of a worldwide effort to discover how genetic changes that increase an individual or family’s risk of developing diabetes may lead to them developing more severe and hard-to-treat forms of the disease - Dr. Robert Sladek, Metabolic Disorders and Complications Program, RI-MUHC

The study led by principal investigator Dr. Robert Sladek along with co-investigators Dr Errol Marliss and Dr Sergio Burgos from the Metabolic Disorders and Complications Program at the RI-MUHC is looking to recruit volunteers to help determine the exact genetic link for the disease. This ambitious project, the first of its kind, is breaking new ground in diabetes research and could lead to some very promising novel avenues to limit this devastating disease and its complications.

If you don’t have diabetes yourself, then you definitely know someone who does. The prevalence of this complex disease is high and constantly on the rise with population growth, aging and increasing obesity driving rates up. Across the globe, 1 in 11 (425 million) people have the disease while 1 in 2 adults (212 million) remain undiagnosed, according to the International Diabetes Federation. Management of this disease remains a challenge as the success of current treatments depend on many factors, including patient compliance with therapy, lifestyle and nutritional habits and tolerance for side effects of certain medications. This global epidemic shows no signs of slowing down as the medical community scrambles to find new avenues to contain the disease.

In what ways could this new research help people with the disease?

“Our study is part of a worldwide effort to discover how genetic changes that increase an individual or family’s risk of developing diabetes may lead to them developing more severe and hard-to-treat forms of the disease,” explains Dr. Sladek.

“If genetic markers are found, this could lead to the development of more effective therapies down the line. More importantly, it could help lead to the identification of people most at risk of developing severe forms of diabetes and perhaps help prevent the disease altogether in patients with milder forms,” adds Dr. Tsoukas.

The idea for the study germinated from an initial discovery by Dr. Sladek and his group of the NG1B gene that is linked to the manifestation of diabetes in muscle tissue specifically. One of the hallmarks of diabetes is the inability of the hormone insulin to control blood sugar levels in tissues. The NGB1 gene plays a role in how muscle cells respond to insulin. The discovery of further genetic markers would help build a genetic profile that could potentially be used to screen people and pinpoint if they are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes and its complications in the heart, blood vessels, kidneys, eyes and nervous system.

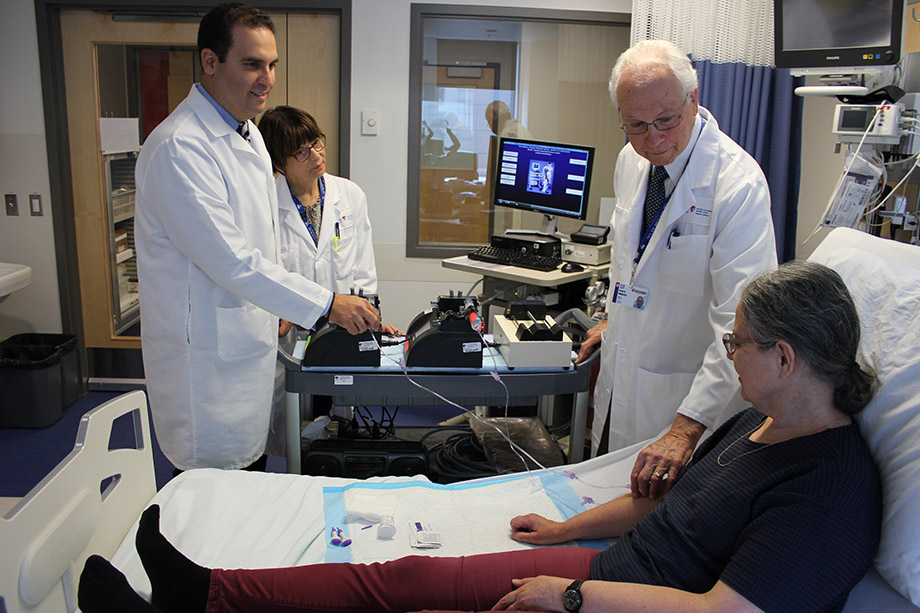

Researchers Dr. Michael Tsoukas, coordinator Marie Lamarche, and Dr. Errol Marliss (from left to right).

“Lifestyle changes and early use of preventive medications could then be developed, to stop diabetic complications before they take hold and cause irreversible damage,” explains Dr. Tsoukas.

The study funded by the US Department of Defence (as a means to help their veterans with diabetes) is a joint effort between partners on both sides of the border, namely the McGill University Health Centre, Genome Quebec and the Massachusetts General Hospital, which is the largest teaching hospital of the Harvard Medical School.

Recruitment has begun for this study that will entail 3 visits to the MUHC’s Glen Site – two visits of a few hours duration and one full day. In all, the research team is looking for 100 participants – 50 with type 2 diabetes and 50 nondiabetic people aged 18-65 years old – and participants will be adequately compensated for their time and effort.

To confirm eligibility to participate, volunteers will undergo several tests, including an electrocardiogram, a chest x-ray and a glucose tolerance test (solely for nondiabetic participants). Once eligibility is confirmed, an insulin sensitivity test and a muscle biopsy will be performed. For the muscle biopsy, a skin incision of only 5 mm long will be made in the thigh muscle once the skin and tissue has been anesthetized. Aside from the use of the tissue results to identify a genetic cause for diabetes, “the samples will be used to create a biobank and stored for future use in other studies,” explains Dr. Tsoukas. Thus, the simple procedure could yield endless clinical research benefits.

Currently, the cause of type 2 diabetes remains unknown. It is believed to arise from a combination of genetics and lifestyle choices. Developing a genetic profile of biomarkers that code for this disease could open up previously unexplored new horizons in diabetes treatment and prevention. Ultimately, this line of study marks the first step in a new direction of research that “holds the potential to yield a completely new category of treatments that target a specific patient’s genetic makeup,” notes Dr. Sladek. In the long-term, the outcome of this research could provide new hope for circumventing this disease and its life-threatening heart, stroke and kidney complications.

To know more about this study please contact the research coordinator Marie Lamarche at (514) 934-1934 extension 35016 or by email at [email protected]