After the Overdose

Heroin fueled the adrenaline that allowed Cecelia Vanier to lug a 200-pound man into the bathtub. The cold shower revived him from eternal slumber. There was no cold water at hand when a young woman succumbed to an overdose in front of Cecelia’s eyes, however. Even now, 17 years clean, Cecelia bolts awake from nightmares of a relapse brought on by the memories of these scenes combined with her own brushes with death from overdoses.

Every spring for 23 years, Cecelia was ambitious to quit. Cold turkey. But the reality of sobriety always prodded her back. In her heart she wanted to stop but didn’t know how. One afternoon stroll along Parc Avenue in Montreal provided an unlikely answer: A friend from her social circle now sitting in a bright restaurant enjoying lunch and, seemingly, enjoying life. She had to go in and ask him how he’d done it, how he’d rediscovered his vigour, found such serenity. He told her he had found the Addictions Unit at the Griffith Edwards Centre (GEC) of the Montreal General Hospital (MGH), McGill University Health Centre (MUHC).

August 31st marks International Overdose Awareness Day, an annual global health campaign aiming to raise awareness, acknowledge grief and prevent future tragedies. The Emergency Departments (ED) of the MUHC received 2,234 visits for toxic effects and/or behavioural disorders due to substance, drugs and/or alcohol overdoses and/or poisoning. The majority – 1,778 – visit the MGH ED, making the GEC well-placed to welcome those who survive with a determination to right their lives.

“The fear of an overdose is a terrible fear. I have nightmares, still. I dream I have drugs on me and I think to myself ‘when did this happen, when did I start using again?’” Cecelia, 61, says. “I wake up terrified. It’s a terrifying feeling to feel this could happen. Such a fate is not an option – I’d rather be dead than go through this again.”

Her own brushes with death provided Cecelia with steely determination. She kicked her heroin habit and began getting her life on track. She went back to school, rediscovered old hobbies. Despite newfound structure in her life, however, the consequences of addiction recovery remained.

“You are expected to feel relief while grappling with depressive feelings and masking your past to all but a few trusted friends and family,” she recalls. “Those feelings of embarrassment, self-loathing, and shame remained.”

The RTP, a Turning Point

Booze soothed some of those emotions, but Cecelia knew she needed to do more. Physically she was improved but she would still need months of emotional therapy to be able to respond to everyday anxieties positively. This critical time when patients are released from the GEC but are still struggling with emotional healing was recognized by Dr. Kathryn Gill, Director of Research at the Addictions Unit.

Dr. Gill teamed up with Ronna Schwartz of the Allan Memorial Institute and recruited Cecelia and other future Peer Mentors to develop a program to fill the void.

The idea for the Recovery Transition Program (RTP), which is part of the MUHC Mental Health Mission, was born. The RTP – which is based out of both the Allan and the GEC – helps mental health and addictions patients’ transition from a clinical setting back into society. The program includes a comprehensive mix of services delivered by Peer Mentors, who are trained and stabilized patients who have lived experience with addiction and/or mental illness designed to help other patients and their family and caregivers find the appropriate support and services following clinical treatment.

The RTP’s Peer Mentor program is essential at a period of heightened vulnerability for patients, providing a turning point in long-term recovery.

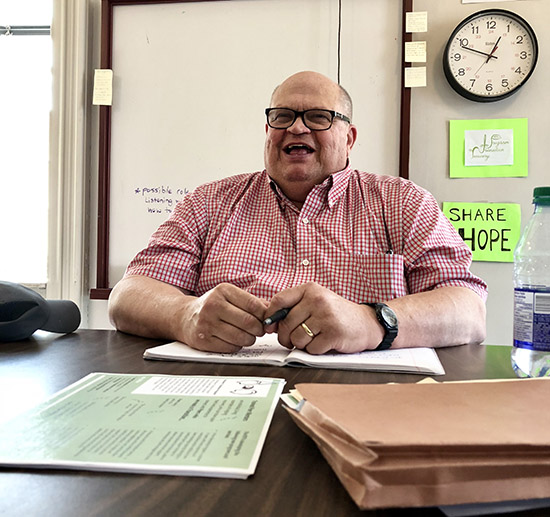

“I struggled with depression and addiction issues for my whole life. What mentors have in common with the mentees is a shared experience. We can talk with people who have issues, they can tell us things they won’t necessarily tell their therapist – and that is very important,” says Bernard St-Laurent, who is known to Montrealers as a political correspondent on CBC Radio, and he oversees the Peer Mentors.

Cecelia and Bernard are among over two dozen Peer Mentors at the RTP, who receive 30 hours of classroom teaching followed by 20 hours of supervision.

Training topics touch on communication and listening skills, boundaries and self-disclosure, dealing with crisis and difficult situations, self-care, role playing and skills practice. Mentors are accepted from several out-patient clinics including Mood, Anxiety, Personality Disorders, Early Psychosis, Psychology, and from the Addictions Unit.

“It’s nothing like the outside perception so we need to help those in need understand how to tackle and deal with their problems. Whether you feel lonely, to how to calm yourself when you’re still depressed, to controlling your urges,” St-Laurent says. “We provide a different relationship to the patient than a physician would, which sometimes makes it easier for them to open up about their problems.”

After surveying patients from these two centres in 2015, it was decided that a program was needed where Peer Mentors would provide education, support and a living example of recovery to patients transitioning from a clinical setting to the community. The RTP went on to win the MUHC Challenge Q+ - aimed at promoting and rewarding innovative ideas for Quality Improvement - and received a grant of $150,000 to bring the program to life. The program has subsisted on the generosity of the Montreal General Hospital Foundation, fundraising and private donations since its inception in 2016.

“The turning point for my long-term recovery has been the RTP,” says Cecelia, who is co-chair of the Fundraising Committee. “It provided the biggest change in my life, left me feeling like I was doing something meaningful. You talk about addictions and problems with the aim of helping others – and yourself. You really help yourself when you do something like this. It’s the first time I felt pride in myself. It’s the first time I’m pushing myself to do things I hadn’t in decades.”

For more information, visit http://recoverytransitionprogram.com or please contact Patricia Lucas, RTP Program Coordinator at 514-934-1934, extension 34544; email: [email protected]

What is an overdose?

An overdose means having more of a drug (or combination of drugs) than your body can cope with. There are a number of signs and symptoms that show someone has overdosed, and these differ with the type of drug used.

Types of drugs that can lead to an overdose:

- Depressants and Opioids: Often prescribed to relieve pain or induce sleep, they slow the nervous central system. When taken in excessive amounts or combined with other drugs, they can depress normal functions like breathing and heart rate until they stop.

- Alcohol: A depressant that is possible to overdose on. Acute alcohol poisoning is normally the result of binge drinking.

- Stimulants: Drugs that increase alertness, heart rate such as amphetamines, cocaine, MDMA. Amphetamine overdose increases the risk of a heart attack, stroke, seizure, or drug-induced psychotic episodes.

What to do if you witness an overdose:

- Call 9-1-1

- Check for vital signs: Is the victim responsive? Breathing? What is the color of their lips?

- Try to get a response by calling their name or rubbing knuckles across their sternum

- If there is no response, place them in Recovery Position

- Do not leave the person alone

- Do not give the person anything to eat or drink; do not try to induce vomiting

Reduce Your Risk:

- Do not use alone

- Know your tolerance

- Do not mix opioids with alcohol or drugs