Pain and infertility, often the face of this obscure disease

Lena Dunham, director and actor in the popular television series, Girls, recently let her fans know that she was taking a little break due to her endometriosis and in doing so launched this not so well-known disease into the limelight.

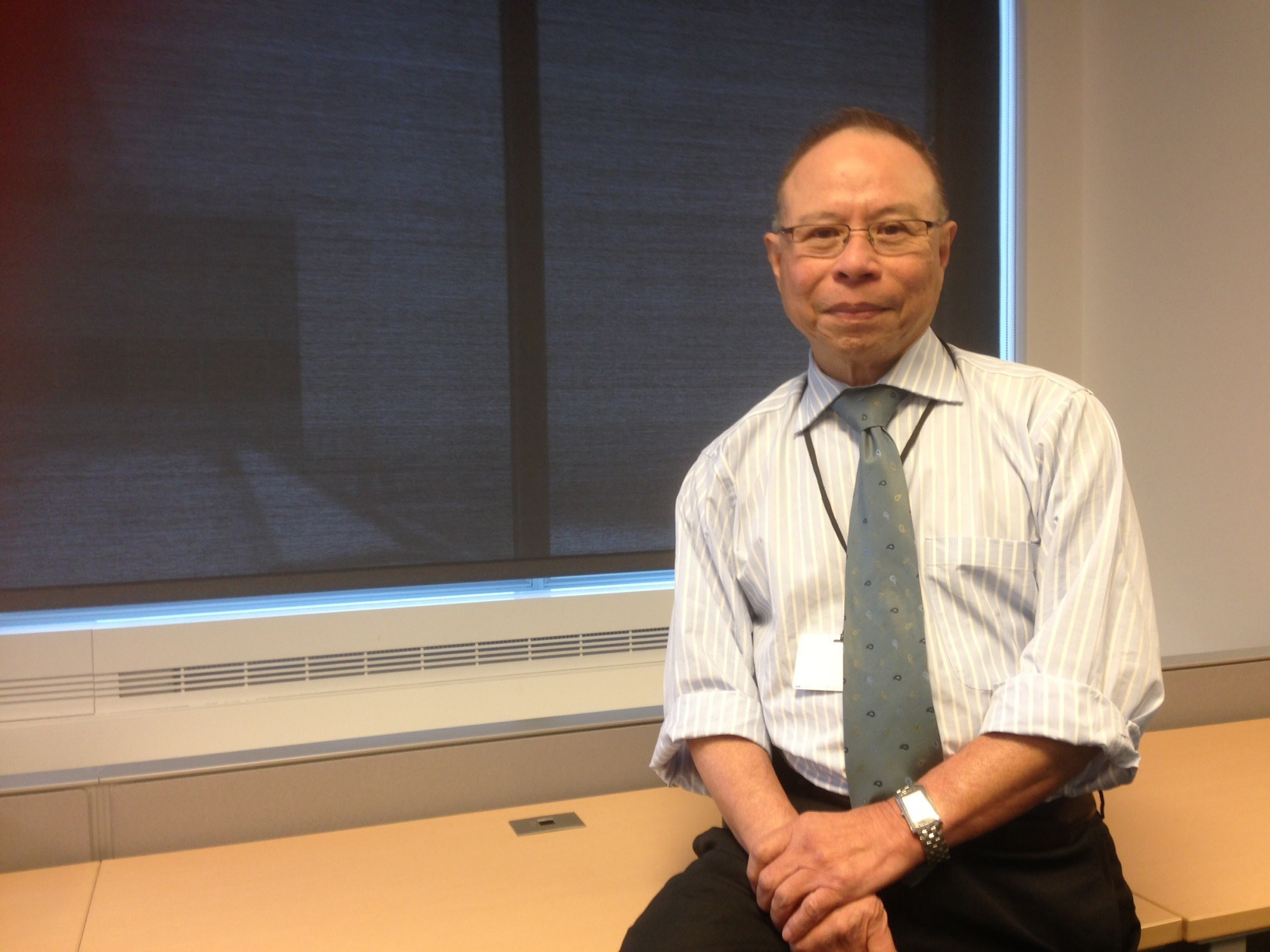

Despite its obscurity, endometriosis affects at least one million women and girls in Canada, and millions more worldwide. “It is a condition that occurs when the endometrium tissue inside the uterus grows outside the uterus,” says Dr. Togas Tulandi, interim chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), and interim chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Milton Leong chair in Reproductive Medicine at McGill University, who also wrote a book on the subject that received much attention. “The growth is usually in the abdomen on the ovaries, the area between the vagina and rectum and the lining of the pelvic cavity.”

In some women, this tissue growth happens without them even noticing. In others, it's a painful, chronic condition. Because the extra tissue that would normally be shed during a period has no way to exit the body—regular uterine lining would shed through the vagina during a period—it builds up and becomes trapped, leading to pain and, in some cases, infertility.

“Often, endometriosis is difficult to diagnose but in women experiencing fertility problems or pelvic pain, 25 to 30 per cent of the time this is the culprit,” says Dr. Tulandi. “Most of the time symptoms include painful periods and intercourse and sometimes pain during a bowel movement. Infertility is a side effect.”

For newly-wed Sarah∗, she had no idea she had endometriosis until she went off the pill to get pregnant. “I was at work one day and I had terrible stomach pain. I didn’t understand what it was,” she says. “I had to leave work because the pain was so horrible. I ended up getting an ultrasound the next day and they could see that I had endometriosis cyst.”

Sarah was referred to Dr. Tulandi, who informed her that because the endometriosis was so extensive she would require surgery to remove the tissue, which would improve her chances of getting pregnant.

“We cannot make a diagnosis with medical imaging for stages 1 and 2 endometriosis,” says Dr. Tulandi. Sarah had stage 4. “Instead, we need to look with a telescope laparoscopically. If endometriosis is suspected we will give medication, which is most often the birth control pill, a medication called Visanne or an IUD, which contains progesterone. These suppress the cell growth, which happened with Sarah, unknowingly, while she was on the pill.”

“If we can control the symptoms with medication I would rather do this than perform surgery,” says Dr. Tulandi. "But if the patient has endometriosis and is experiencing infertility due to the extra tissue, we will operate. This is a minimally invasive procedure and the patient can go home the same day. Trying to conceive right after the surgery is the best time because the cells grow back. They stop growing only after menopause.”

Dr. Tulandi is always looking at what’s new in treatment for patients with endometriosis. Currently, he is on the organizing committee for a 2017 World Conference on endometriosis in Vancouver. “We gather to share knowledge,” says Dr. Tulandi, who is also a fulltime professor with McGill University. “I can then pass this on to my students if relevant, who come from all over the world. In fact, I was recently invited to Israel and met about 10 people I trained.”

For Sarah, the surgery worked well. Within four months she was pregnant with her first child, who was born in April 2012, and two and a half years later she gave birth to her second.

“In between pregnancies, I breastfed as long as I could and took a low-dose birth control pill to prevent the cells from re-growing,” says Sarah. “I am now back on a regular birth control pill as we don’t want more children. I am very thankful for Dr. Tulandi’s care, which was wonderful throughout.”