Shaken Baby Syndrome kills

Levi is one day old. His hair is blondish red and he is sleeping on his mother’s chest, skin to skin. Mom and dad, Suzy and Andy DiBiaso, are visibly euphoric about the arrival of their third son. They will leave the Royal Victoria Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) by tomorrow, but before they go their nurse will take five minutes to teach them about Shaken Baby Syndrome.

In March of this year a teaching program was implemented at the MUHC to educate parents about Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS)—a syndrome that results from an adult violently shaking a baby. The baby’s head bounces about in every direction, which causes his/her brain to bleed and swell. When brain cells burst they never heal. The documented incidence of shaken baby syndrome is about 1 in 200 in Canada. One out of five will die, while the others could become mentally or physically disabled, blind or paralysed. Other problems could arise as the child gets older. About 25 to 50 per cent of parents or future parents do not know that shaking a baby can lead to serious brain damage and death.

(Left to right) Front-line nurses Alexandra Lavoie-Richer, holding the doll, and Diane Viveiros, receive coaching from Anna Balenzano and Linda Boisvert on how to educate new parents about Shaken Baby Syndrome.

Anna Balenzano, assistant nurse manager, with Linda Boisvert, clinical nurse specialist, both of the MUHC Postpartum Unit, Women’s Health mission, received training on how to educate front-line nurses to teach new parents about SBS and to also help them develop a plan of action if they feel they could shake their baby. Over eight weeks, 96 front-line nurses received three hours of training.

The training program is based on research that Ste-Justine Hospital in Montreal conducted, which looked at teaching versus not teaching parents about shaken baby syndrome and its outcomes. The results were clear: education and awareness leads to fewer incidences.

The MUHC nurses were first taught about, and the statistics of, SBS; then the anatomy of the brain was explained and what happens when a baby is violently shaken. What causes people to shake their baby—a persistent phase of crying—was also outlined.

“The final point is important because parents need to understand that crying in newborns is normal. Colic is a myth,” says Balenzano. “Crying results from a normal neurological development of the brain. Parents may have a baby that cries more than three hours a day, maybe more than three times a week or for more than three months and that is normal. We tell them that it is natural that they will get angry. What is not okay is to shake the baby—they have to find strategies to control their anger.”

The nurses had to pass quizzes associated with their learning. They were nervous at first to include the teaching into their daily routines as they feared the reaction from parents would be negative, but the opposite happened. Parents have overwhelmingly welcomed the five-minute teaching sessions and the take home material that explains what Shaken Baby Syndrome is, what is normal in terms of crying, how to understand their anger and a plan of action if they ever get so angry they feel like they will shake their baby. And there is a help-line available if the parents have no one else to call during the crisis.

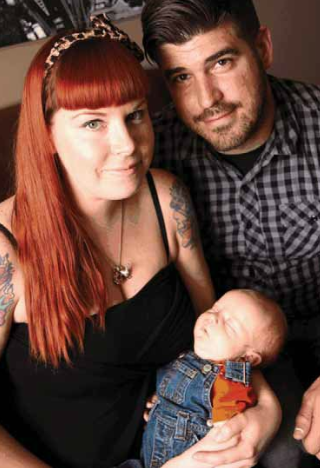

Suzy and Andy DiBiaso with Levi.

Suzy and Andy DiBiaso with Levi.“In the beginning it was hard, getting used to what to say, but now I can go in and talk about it without having to look at my cards,” says Diane Viveiros, a nurse who works in the MUHC Post Partum Unit. “I have had good reactions every time and all parents have been very surprised by the information. Yesterday, a father said to me one of the things that really stayed with him was that there is not a type of person who does this, it can be anyone.”

For Suzy DiBiaso, she appreciates the teaching. “I am sure some people think they may never get to this point. This is my third child and I know it can be emotional; babies cry and if you have a baby that is inconsolable and you are exhausted, and on top of it, hormonal, it is sometimes challenging and tough to be level headed. I like the plan of action that is encouraged. I personally have never reached this point, but I think everyone is capable of having an emotional burn-out.”

“To deliver quality care to our patients and families, MUHC nursing practice constantly changes due to evidence based research,” says Balenzano. “If we save just one life, improve just one child’s outcome, we know we are doing a good thing.”