Nunavimmiut public health officers offer TB outreach in Nunavik, Quebec

March 24 is World TB Day – we checked in on a recent training session in Inukjuak by Indigenous researchers and health professionals for Inuit community members

SOURCE: McGill University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

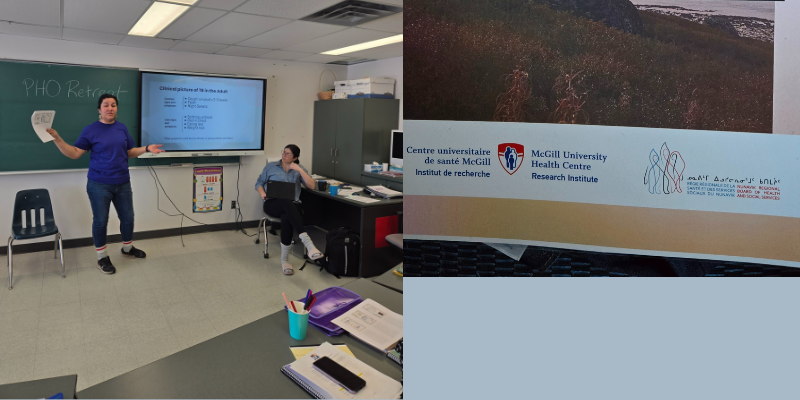

A community-based public health initiative to support Nunavimmiut (Nunavik Inuit) with tuberculosis (TB) got a boost in February when a training session for five new Nunavummiut public health officers (PHOs) took place in Inukjuak.

The PHO role was recently developed by the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services (NRBHSS) and the region’s two hospital networks to make space for Nunavimmiut to be directly involved in providing public healthcare related to tuberculosis – which has seen increasing incidence in Nunavik since 2003 – and other conditions. The initiative is part of the ongoing Nunavimmiut community strength and empowerment movement towards greater self-governance.

The training session was offered by the team engaged in a parallel research project at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (The Institute) co-led by Glenda Sandy, RN, MSc, a Naskapi-Cree nurse advisor with the NRBHSS, with Faiz Ahmad Khan, MD, Scientist in the Translational Research in Respiratory Diseases Program at The Institute, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine at McGill, and a respirologist practising in Nunavik and Montreal. The team that led the training session development also includes Ben Geboe, LMSW, PhD, member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe (Dakota) with family in Manitoba First Nations communities, social worker and postdoctoral fellow at the The Institute, and Anna Dunn-Suen, MSc, research assistant in the The Institute’s Respiratory Epidemiology and Clinical Research Unit.

“Kanniq means ‘confluence’ in Inuktitut and is a traditional place name in Nunavik where two rivers meet,” explains Sandy in reference to the program name and her official job title, Kanniq Team Coordinator (previously PHO Training Coordinator). “That is the foundation for the PHO program where Nunavimmiut voices and experiences are shaping and guiding its development based on their experience with tuberculosis and in what they hope to see in their communities. Kanniq team members work very closely with PHOs in meeting them where they’re at and offering training and support in navigating their professional growth at their own pace.”

Adds Dr. Khan: “Our team, under the guidance of Puvaqatsianirmut (our steering committee) and our Nunavimmiut partners, tries to use research as a tool for allyship. In this instance, we had the opportunity to support Nunavimmiut-led efforts for greater Inuit self-determination over tuberculosis services.”

The research involved a major consultation with almost 150 Nunavimmiut by Geboe and Nunavimmiut community researchers Sophie Tukalak, Daphne Tooktoo and Natasha MacDonald (PhD). In interviews, predominantly undertaken in Inuktitut and in Nunavik, Nunavimmiut shared their expertise and experiences on their communities and on tuberculosis. The results are being used to not only inform the program, but to provide tools for the PHOs.

Last month’s training session, led by Sandy, Geboe and Dunn-Suen, included five PHO trainees from three communities that are currently experiencing active TB clusters. The team introduced the trainees to the TB manual they developed based on the consultation, which was very well received by the trainees and community members.

The PHOs will work with TB nurses in their communities to offer support and guidance to TB patients. “There's an array of clinical functions that they might contribute to, but a major role is supporting people and families, even with understanding what they are going through,” explains Geboe. “So some of the manual was about TB and various interventions, and a major part was community engagement and communication.”

Geboe, who has a long history of doing community outreach with urban Indigenous populations in Montreal and New York and was able to adapt some of this to the PHO training, explains that social work engages in a kind of approach to public health called mutual aid. “The best people to do this kind of work are people that have the actual experience of the community that you're trying to address,” he says. “In the case of the PHOs, some of them have experience with TB through family, friends and they’re very passionate about their community. And they speak Inuktitut.”

In addition, the involvement of a consistent group of Indigenous team members has been one key to its success. “I personally draw a lot from my own lived experience as the first Naskapi nurse in my community, working and walking in two worlds, to help guide the work I do,” says Sandy, who has been an RN for 22 years and with the NRBHSS since 2019; she has also served as an Indigenous Nurse Advisor with McGill’s Ingram School of Nursing.

“I think one of the strengths of our approach is its continuity,” adds Dunn-Suen. “The researchers who interviewed participants were actively involved in the conception of the manual and the training. It is still early days, but I feel that contributed to how well the training and manual have been received.”

The team is hopeful the program will be expanded to encompass other public health issues. “I'm hoping that this will be that future resource when they're doing assessments on health needs. One of the inspirations was the wildly successful midwifery program in Nunavik,” says Geboe, adding that by creating employment, the PHO program is contributing to the local economy as well.

Ultimately, says the team, it is important not to lose sight of the big picture aims for communities in Nunavik: namely, Nunavimmiut taking the lead in deciding how to approach their healthcare needs.

One piece of wisdom, shared by both a Nunavimmiut elder and community leader during the training session, really resonated with Geboe. “They said: ‘It doesn't matter if somebody takes treatment or they reject it. What matters is that they’re deserving to be offered the treatment,’” he recalls, explaining that in our quest for outcomes this more inclusive goal can be lost. “We think: ‘What's the outcome? They got the meds.’ We always see the end. But what they talked about – and this is a very Indigenous point of view – is that we should continually engage, even if a person won't even look at us,” adds Geboe. “That was so crystal clear, ethical.”